State of the Game: New Ways to Think About an Old Game

EMBRACING CHANGE LEADS TO GROWTH

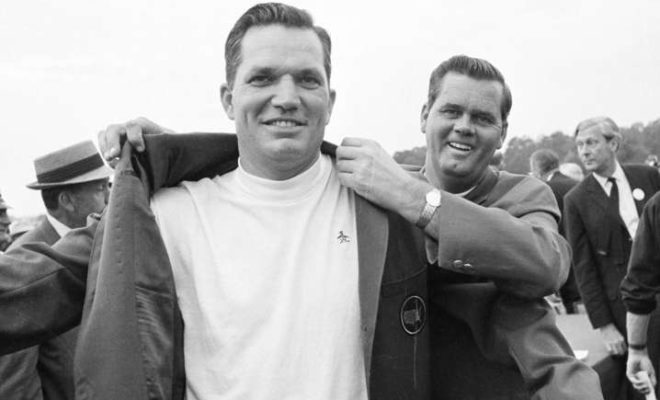

IT WAS A WATERSHED YEAR for the addiction of golf. New rules took effect, green-lighting any number of once-clandestine practices many of us long ago adopted. The post-Tiger generation continued to grab headlines. And that Tiger guy pushed back against time yet again.

The game feels like it has mojo yet again.

Who could ask for more? Any sane person, that’s who.

We’re in an era of doom and gloom, and the bandwagon message from corporate boardrooms to glossy sports pages is that golf is hemorrhaging. Stop. Step back. Breathe. Golf is not dying, it is not on life support. Sure, the industry overextended, overbuilt and overestimated. In sports parlance, golf outkicked its coverage.

But the hysteria?

“We’re OK,” says Craig Kessler, the Southern California Golf Association’s director of governmental affairs. “The last 10-plus years have not been great, but the market was long overdue for a correction. With that in mind, this is what I would change: The message. We’ve turned to denigrating the product we are trying to sell. The message is that the game is too stuffy, too demographically limited, too hard, too expensive, too time-consuming.”

“What of the enduring strengths of the game? Nature, leisure, respite, social interaction, challenge. Those are the game’s core strengths. We need to market to those strengths. The allure of the game is precisely because it is a challenge, it takes place in nature, it changes daily — it’s not in a bowling alley — it’s a break from the 24/7 world and the smartphone. Let’s acknowledge those values and turn the message toward them, not make them out to be weaknesses.”

RIGHT-SIZED RELEVANCE

Course architect Damian Pascuzzo rattles off a decidedly radical (and refreshing) concept: “I would do away with the concept of par.”

“Par,” as in an expected score for an accomplished player on a particular hole, might not sound so devious. But it spawned institutionalized beliefs that for many verily came down from Sinai etched in stone: “Real” courses have 18 holes; a par of 72 dosed out across 10 par 4s, four par 5s and four par 3s; and three or four teeing grounds identified by red, white, blue and black, if there is a fourth, and yardages of 5,700, 6,100, 6,600 and something that damn well better go way past 7,000.

There are handicap-calculation implications to getting rid of par. There are sacrosanct historic contexts — although does anyone really wanna argue relevance when Hogan hit 1-iron and the same hole now sees McIlroy with a 7-iron? It does allow for a quick snapshot of who is where, in a relative sense, at any point in a stroke-play tournament.

“Par provides such a hang-up for so many people,” Pascuzzo contends. “The idea of par gets in the head of too many amateurs and it prohibits them from enjoying the game. It also impacts course design. Some developers don’t believe they have a real golf course unless it is par 72. That is just ridiculous. You might be able to design 18 better golf holes that add up to a par of 70, or 68, but they aren’t interested.”

OK, here’s saying par sticks around but it needs to let go of the measuring tape. Right-sizing courses, which is becoming a bigger part of the design business, goes toward that end, and it would put more real-world relevance into what par means on a specific hole (and perhaps speed up the game and perhaps chew up less land and perhaps lower costs and …).

Right-sizing means admitting that standard conventions for what we think constitutes a “proper” layout are outmoded, based on real-world data on how far most of us (don’t) hit the golf ball. We need to move forward, often a long way; white might be just right at 5,900 yards. But for many that is like challenging the queen’s virtue. And the greatest disservice is being done to those who play at the front end of the course, where accomplished but slower-swinging players seldom find the sub-5,000-yard tees they need.

Pascuzzo has been designing tees on either side of 4,000 yards, and they’re being embraced, for the simple reason that for all the marketing millions, most shots don’t go far.

“With these tees we have players experiencing golf as it is meant to be — a reasonable expectation of reaching in regulation, having a birdie putt here and there, perhaps for the first time. Asking some folks to play a 5,500-yard or longer course might be too much. They know how to play golf; they simply don’t hit the ball that far. It would be like a Tour pro playing from 9,000 yards.”

GRASS ROOTS

“The game is rather healthy,” says Brandel Chamblee, one of the most outspoken voices in golf, “though of course there always are ways to make it better.”

Echoing Kessler’s sentiment that we need to embrace the values and traditions of the game as a means to bring more people in, Chamblee sees this as a grassroots issue, and quite literally. Most of us came to the game at a club or a muni, or even a range. We were kids or young teens, and we liked to screw around, of course, but we had oversight. If we’re in our 50s, 60s or ages even better than those, chances are there was some tutelage and structure to our time on the grass or mats. And that has been lost, to some extent, or at least the oversight has shifted.

“There needs to be an understanding of the effects of corporatization of the game, the monetizing of every aspect of the game,” Chamblee says. “Profit is not a bad thing. It just needs to be poured back into the roots of the game. That is how you grow the game.”

Chamblee sees golf at the level of the modern club or course too often as business operation first, golf and instructional operation second. Spreadsheets, specialization and compartmentalization, and corporate expectations have taken much of the grass roots of golf out of the green-grass operation. Courses still offer golf, pros still teach, but not to the scale or with the level of involvement we once saw as nearly ever-present, and notably at the starter level.

Much of this needed tutelage and guidance has been taken over by the myriad junior golf programs, often competitive, that now exist, and Chamblee has high praise for efforts such as SCGA Junior and specifically the First Tee, with its educational and character-building curriculum woven through with the values inherent in our game.

“These junior programs change lives. It is doing what golf professionals used to do at the club. And not just playing golf; it’s the social skills, sportsmanship, patience, responsibility, communication, etiquette. This once existed at a localized level, in every town. It was the local pro.”

SHARED EXPERIENCES

Millennials, good luck to you. You’re said to be insecure and to lack a work ethic, that you can’t act or think for yourselves and, sin of sins, you don’t like golf. Don’t worry: Your elders were hippies. You should see what was said about them, and they turned out fine.

“Too many in the game deride the millennials, who are the group that could step up for the game,” advises Kessler. “But we blame them for being too aloof and not focused. We need the millennials. We just have to present the game with its many positive traits and challenges but without the old trappings. We need to let the game present itself as they want it to be.”

Study after study about Millennial habits and preferences puts shared experiences at the top end of the must-have list. For all the solitude and introspection golf can provide, the game is hard-wired toward collegiality and a shared community of kindred spirits with whom to share the birdies and the more common blow ups.

“Millennials? They’re highly engaged in golf,” says Henry DeLozier, a partner with think tank and consultancy Global Golf Advisers.

WE NEED THE MILLENNIALS. WE JUST HAVE TO PRESENT THE GAME WITH ITS MANY POSITIVE TRAITS AND CHALLENGES BUT WITHOUT THE OLD TRAPPINGS. WE NEED TO LET THE GAME PRESENT ITSELF AS THEY WANT IT TO BE.”

Contrary to the too-common misconception, millennials show a high propensity for interest in golf. Now, golf for them might be TopGolf or a three-hole glow-ball outing on a Thursday night with a different local brewer slinging suds on each tee, yet TopGolf is touted as the leading conduit through which beginners or otherwise non-golfers head over to the game proper.

Tweaking an old Rodney Dangerfield gag, DeLozier quips, “I went to a drunken fraternity party and a PGA Tour event broke out.” He’s speaking of the Waste Management Phoenix Open, of course, and while not exactly how he’d choose to watch a tournament, it’s a formula that works for many. The sport and its rituals certainly have lightened up, and the portals have been expanded. We can do better and we all need to remember that the way we might want to experience something is not how everyone else wants to experience that same activity.

“If those fans in Scottsdale think that is fun and it brings them to golf, good for them, and good for all of us,” DeLozier says. “Who am I to tell the next generation how to embrace the game?”