An Enduring Legacy: Celebrating 100 Years at Brentwood CC

She called the new “Double Circle Golf Course” a novel design, with the front nine starting and ending at the clubhouse and the second surrounding the first in an even wider ring. Near the Pacific, “it will be the only country club hereabouts that can boast ocean plunges within five minutes, the Santa Monica sea proving no small adjacent asset.”

In the January 1916 Los Angeles Daily Times feature about the Brentwood Country Club’s prospective opening, the 350 charter members were all described as matriarchs of a type, including “important financial mothers, shining legal mothers, ordinary millionaire mothers, distinguished tennis mothers, starry golf mothers, shrewd business mothers (and) numerous British bowling queen mothers.”

Alma Whitaker, a prolific and pioneering reporter, could layer on the hyperbole thicker than Rudy Valentino’s makeup.

Very little about Brentwood’s origins would exist without Whitaker’s spirited journalism. She also chronicled its opening later that year. Starting with nine holes, the “debutant country club,” as she put it, also made use of three private tennis courts, “available by the magnificence of President Thomas Bundy.” Initially referred to as the Santa Monica Country Club and at times as the Santa Monica Tennis Club, the 160-acre property also intended to offer polo, although it ultimately failed to revive a sport that had thrived in the area 20 years prior.

The golf course marks its centennial in 2016, and although the milestone may pass unobserved. Today’s Brentwood CC traces its incarnation to 1948, when a group of largely Jewish investors purchased a failing public course and reopened it as an alternative to the Hillcrest CC, at the time Southern California’s only Jewish country club, but which had a full membership.

Today a thriving and multifaceted club with golf, tennis, a fitness center, swimming and more, Brentwood has roughly 700 members. “Our average age is 61, although that’s somewhat deceptive,” explains Rosemary Bryan, Brentwood’s membership director since 1992. “We’ve had a large number of young families join in recent years. But there’s also an unusually large contingent of very active and healthy people over 90, which skews up the average.” On a weekday afternoon a visitor could briefly mistake the clubhouse for a senior center, but on a Sunday afternoon one will find it jam-packed with children.

Brentwood’s younger demographic is having other influences as well. “Our dress code seems to be more casual than at other clubs,” observes Bryan. “Denim is permitted in every dining area. Fine dining is not the priority that it once was, because the members just don’t want to dress up.”

HOLLYWOOD MOMENTS TALL TALES

The evolution of the dress code is a mild shift for an institution that’s gone through many changes over the years. Like most venerable clubs in Southern California, Brentwood has its share of conflicting stories, Hollywood moments and cluttered design provenance.

“It gets very confusing,” explains golf historian John Jones, a Grammy-winning record producer, musician and songwriter who has spent a great deal of time cataloguing the sport’s origins and development in California. “Willie Watson is credited with being the original architect who sketched a routing, but without aerials from that era it’s hard to tell. During construction the club also had two top amateurs as advisors, Norman Macbeth, the Royal Lytham & St. Anne’s champion, and Scotty Armstrong, one of the better golfers in Southern California. Tom McCall, who was the club’s first vice president and head of the green committee, probably also had input on the design.”

“It gets very confusing,” explains golf historian John Jones, a Grammy-winning record producer, musician and songwriter who has spent a great deal of time cataloguing the sport’s origins and development in California. “Willie Watson is credited with being the original architect who sketched a routing, but without aerials from that era it’s hard to tell. During construction the club also had two top amateurs as advisors, Norman Macbeth, the Royal Lytham & St. Anne’s champion, and Scotty Armstrong, one of the better golfers in Southern California. Tom McCall, who was the club’s first vice president and head of the green committee, probably also had input on the design.”

Bordered by Montana Avenue, South Burlingame Avenue and San Vicente Boulevard — the latter of which paralleled a rail line between Los Angeles and the Southern Pacific Wharf in Santa Monica — the 130 acres selected for the golf course were not particularly suited for subdivision, due to a deep barranca that weaves through the property. The first nine holes opened with a tournament on March 25, 1916, with the second nine opening the following year, playing to an estimated 6,000 yards.

Because Brentwood had limited access to water, Watson’s design featured putting surfaces fashioned of oiled sand, common in that era. They were flat and true. “But Brentwood wanted to be part of Los Angeles instead of Santa Monica, because L.A. had water,” explains Jones. “They voted for it, but it took a court case to make Brentwood part of Los Angeles in 1918. We don’t know exactly when the pipes came.”

They were, however, there by 1921, when the course was entirely rebuilt under the direction of architect George Merritt, who changed the layout and installed grass greens, which had contours not found on sand surfaces. “It took two years but in 1923 the new course opened,” says Jones, “now playing at 6,400 yards.”

In 1925, architect Max Behr arrived, and according to Jones found 51 different types of grass on one of the greens. “They really wanted to host the inaugural $10,000 Los Angles Open in 1926,” says Jones, “and Behr was going to make sure the course was awesome. He added 50 new bunkers, moved some fairways and rebuilt seven of the greens. But The Los Angeles CC got the event. Brentwood was apparently too far out of town and not quite ready.”

Consolation came that year when Brentwood opened the doors of its $200,000, two-story, 30,000-square-foot clubhouse, featuring Southern California Spanish architecture and views overlooking the entire golf course. The building’s second floor had 21 hotel rooms, which are today used for storage and as offices. Showers, locker rooms and the pro shop were in a spacious basement. While the building has been enlarged, remodeled and redecorated numerous times, it sits on the same footprint as the original.

TALL TALES AND CHANGING TIMES

Not long thereafter the club hired the most famous head professional in its history, Olin Dutra, who remained there until 1935. Known as King Kong and the Slammin’ Spaniard, the 6-3, 230-pound Dutra won two majors while playing out of Brentwood, including the 1932 PGA Championship and the 1934 U.S. Open. He also played on the 1933 and 1935 Ryder Cup teams, and brought pals like Bobby Jones to the club.

Dutra is even better known for a 1932 stunt, where he famously gave future SCGA Hall of Famer Babe Didrikson “a two-minute lesson” at Brentwood, before she played her “first” round of golf. Babe proceeded to blast her tee shot some 240 yards, well past her male playing partners.

“But it was all hype,” says Jones. “Her group included Grantland Rice, and three other sportswriters. And it was a lie that she had never played. She’d been golfing for a couple of years.”

The Depression took its toll on Brentwood, as members left the club, loans were defaulted and back taxes piled up. In 1937 the property was purchased by William Bryant, who during that decade bought a number of troubled courses and attempted to keep them running as daily fee operations. “When the place became a public course, all of the main Brentwood members moved over to Riviera,” says Jones. “According to SCGA records, Brentwood fielded a public links team in 1939 and 1940.”

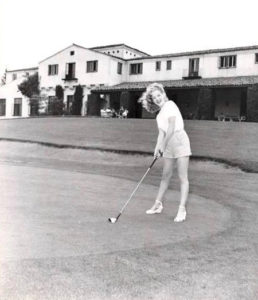

But the track didn’t die easily. There’s a photo from Twentieth Century Fox-sponsored tournament held at Brentwood in 1947 of young starlet Marilyn Monroe in one of her first gigs. With blond hair flying in the breeze she’s wearing shorts, high heels and looking adorable teeing it up with a driver on a putting green.

Nonetheless, the public course wasn’t profitable. “The owners were prepared to sell the land for a housing development,” says Bryan. “By then the area was hugely populated.” A number of developers considered buying the property for housing, including Edward Zuckerman and Arthur Edmunds. But the men who eventually became the first and second presidents of the reinvented Brentwood had another idea.

Most private clubs in greater Los Angeles at the time did not accept Jewish members. In response, Hillcrest CC formed in 1920 as the first almost exclusively Jewish club in the area. It attracted many of Hollywood’s biggest stars, including Jack Benny, Danny Kaye, George Burns and, among others, Groucho Marx. And it’s apparently where Milton Berle stole many jokes.

With Hillcrest’s membership roster full, Zuckerman, Edwards, Ben Weingart and Irving Siegel began negotiations to buy Brentwood, instituting a family-centric policy that discouraged heavy gambling and drinking. “The club will be a place where a husband will come with his wife,” said Zuckerman, “rather than a place he will come to get away from his wife.” Another policy was that it would not be exclusively Jewish. The club’s history notes that a restrictive policy “was inherently wrong.” They also made it clear that if any prospective member weren’t predisposed to a “friendly and congenial social relationship with Jewish persons,” they probably shouldn’t join. Closed to the public in the summer of 1948, Brentwood CC reopened as a private club.

It was, if you’ll pardon the use of the term, born again.

Today, about 97 percent of its members are Jewish, which means the other three must be down with the high holidays. Says Bryan with a laugh: “It’s probably more important that they’re comfortable around a lot of kids.”

RESTORING A CLASSIC

Brentwood hosted the 1950 Western Open, won by Sam Snead. Snead also came back to film several episodes of Celebrity Golf, where he competed in nine-hole matches for charity against amateurs such as James Garner, offering quips and tips.

The course was also slated to host the 1961 PGA Championship. But when California State Attorney General Stanley Mosk learned of the PGA’s Caucasian only policy — which the organization later dropped and has gone to great lengths to make amends for — he fired off a letter that caused the PGA to move the tournament to Olympia Fields in Illinois.

The course was also slated to host the 1961 PGA Championship. But when California State Attorney General Stanley Mosk learned of the PGA’s Caucasian only policy — which the organization later dropped and has gone to great lengths to make amends for — he fired off a letter that caused the PGA to move the tournament to Olympia Fields in Illinois.

That was the end of major events, says Brentwood head pro Patrick Casey, and the beginning of a lower profile for Brentwood. “Unlike Riviera, Bel-Air and other clubs in the area that have a lot of famous members, our membership tends to be more subtle and laid back. We just don’t have the A-list celebrities. But we do have the agents, producers and the behind-the-scenes people who make Hollywood go.”

A parklands layout that’s easy to walk, Brentwood, like all golf courses, is always a work in progress, says Casey. In and out of disrepair, a long line of architects continued to put it back on track. Desmond Muirhead handled one remodel. John Harbottle oversaw the next, a full restoration in 2004 and 2005, with a master plan including still more changes.

After Harbottle’s death in 2012, the club turned to Todd Eckenrode, who developed plans that built upon Harbottle’s. “Todd refurbished the practice area, took out more than 300 trees, and managed our turf reduction project and the conversion of greens from poa to bent grass,” explains Casey. “Turf reduction is a huge issue given California’s water issues.”

Equally important to the look of the course was bringing back what some call “the canyon,” or the barranca that runs about 20 feet deep. “It’s a defining feature of this landscape,” says Eckenrode. “Seven holes play across it, and the 16th green is essentially a peninsula, surrounded on three sides by the canyon. Over the years, however, grass and shrubs had grown up to three feet tall in much of the barranca. It eased the load on maintenance, but rendered it unplayable. So we did some grading and seeded it with fescue so that it will look wild, but will have definition and still be part of the course.

Finally, Eckenrode pulled a number of bunkers back and away from greens. “Bunkering got awfully predictable during the 1950s and 1960s. Every one had to be at the edge of the green, with one in the front and to the left, and other to the back and right.”

Since most of the bunkers on the course were the same size, Eckenrode enlarged some and added others. “More important is that we pulled a number of them back and away from the green, which changes the player’s perspective on approach shots. It’s something that you would very often find on the courses from the 1920s.”

That’s also when an Alma Whitaker could spread the flattery thick, writing in the Times about Brentwood’s house-warming party: “The social eclat of the occasion was all that could be desired and the jolly little clubhouse simply oozed class. The tea table alone was worth the visit (with) regal cake dishes, bread and butter trays galore.”

The “millionaire mothers, starry golf mothers, shrewd business mothers (and) numerous British bowling queen mothers” may be long gone, but today’s generation of soccer moms and their families are doing quite well at Brentwood Country Club.