One With the Land: Sustainability Actions Speak Louder Than Words

If you think the sand in the 17 bunkers at The Ranch at Laguna Beach golf course has a slightly greenish hue, you’re right. The color comes from an onsite program that recycles bottles into sandy material that is then used to augment existing bunker sand. It’s just one example of ongoing sustain-ability efforts at courses throughout Southern California, primarily driven by environmental concerns, water usage issues, and budget considerations.

How are those being addressed? With new types of more drought-tolerant grass, in-ground moisture sensors, organic gardens and even Monarch butterflies.

WATER WORKS

“I don’t use the word ‘sustainability,’” said Wayne Mills, superintendent at La Cumbre CC in Santa Barbara. “I use the words ‘reduced inputs that benefit society.’ Potable water is a fluid people need to sustain life,and we were using it to irrigate turf. If we use reclaimed water, we use less potable water and still employ people, create living wages, and give people a place to enjoy themselves.”

At many courses, the water budget can run from $250,000 to $1 million a year. Even a 10 percent savings can be significant. That’s why courses are keeping a closer eye than ever before on water usage.

“In addition to using portable moisture meters (usually on putting greens, which represent 3-4 acres of turf overall), we’re seeing a trend for courses to install in-ground moisture sensors in fairways, which typically cover 25-35 acres, and even roughs (25-50 acres),” said Brian Whitlark, Sr. consulting agronomist, Green Section, USGA. “To increase water savings, those are the areas that need to be focused on.”

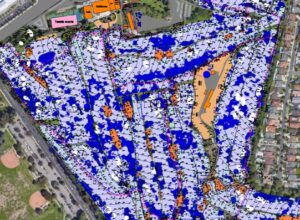

At Hillcrest CC in Los Angeles, which underwent a renovation by course architect Kyle Phillips in 2019, a property audit identified dry and wet spots on the 95 acres of irrigated turf. That information was then programmed into the irrigation system to match soil characteristics.

“We irrigate only what we need to irrigate,” said Matt Muhlenbruch, director of agronomy at Hillcrest. “The next phase is to install a soil moisture sensor network in each of the eight areas we have broken the course into. We’ll know exactly at what point the grass begins to wilt, how much we need to irrigate, and for how long. We will have better control over those wet and dry spots and will see water savings.”

La Cumbre CC recently finished a $1.3 million project that brings reclaimed water to the property across three boundaries (city, county, and ranch annex.) Using that type of water for an estimated 90 percent of irrigation will bring costs down, according to Mills.

“People without a vested interest see all the green turf, but now there are reclaimed water signs around the course explaining that water that would have been just dumped into the ocean is now used for irrigating the property as we move forward,” he said.

Mills has also worked with a local biologist to identify turf replacement options.

“So far we ‘ve taken out 14 acres of turf in rough areas and brought in native plants enhanced by wildflowers, California poppies, and lupines to attract specific species, like bumblebees. Our members look forward to a super bloom each spring when the areas really light up.”

While turf reduction seems like a no-brainer when it comes to reducing costs, there is a catch.

“Generally in California, the turf requires anywhere from 3.5 to 6.5 feet of water per year, per acre,” said Whitlark. “If you are able to remove turf and put in low-water-use landscaping (which could survive with minimal irrigation in coastal areas), then the challenge is you do save on water, but you might not save on labor. What we have found is that you need to add staff because those non-turf areas require either as intensive or more intensive maintenance in terms of weeding, pruning plants, removing dead plants, using herbicides to control weeds, etc.”

And labor has become a huge issue during the pandemic. “I don’t know a golf course right now that has a full staff,” said Muhlenbruch.

“I have a lot of discussions with equipment providers about autonomous mowers to alleviate some of the labor shortage. Also, with a lesser head count, we could provide a higher-paying, more sustainable work force and still get the job done. And we don’t have a lot of turnover here (at Hillcrest CC). Your water supply is more consistent than the labor supply.”

TURF TALK

“Pretty much all the courses I know of in metropolitan Los Angeles have Bermudagrass fairways and rough, and they’re not overseeding, which is a good thing from the standpoints of water conservation and Poa annua control,” said Dr. Jim Baird, turfgrass specialist at UC Riverside. “The change has been made, so to speak, from cool-season grasses to warm-season grasses. Ultimately we’re going to produce grass that is better than what they have, but to move from Bermudagrass to another Bermudagrass will take something special, and we’re not there yet. But I believe someday that will happen. We will have the grass stay greener and use less water.”

This year Baird and his team will release two new Bermudagrasses that have been in development since 2013. Each is designed to have better color in the winter months, relative to the course location, and be more drought resistant.

“All the courses I have talked to in California say that conservatively, they save 25 percent more water when they make the conversion to a hybrid Bermudagrass,” said Whitlark. “They have demonstrated for many years not only significant water savings, but also savings in chemicals because you don’t need the fungicides or fertilizer that you need with the hodgepodge of grasses that have evolved over time at many courses. On top of that, the golfer experience is much better with improved year–round playing surfaces.”

SAND SAVES

Give Kurt Bjorkman credit. Back in 2016 the general manager at The Ranch at Laguna Beach read about a New Zealand company that built a machine to crush recycled bottles, filter the remnants, and create usable materials, like sand, that could be used to help shore up beach erosion. He wondered if it could be used to create sand for bunkers on the resort’s public nine-hole course. The answer was yes.

“Sand is a really problematic resource right now,” said Bjorkman. “It’s the third most widely used resource in the world behind air and water. Sand is in everything.”

For an investment of less than $20,000, the results have been impressive. “In 2019 we crushed 70 tons of sand just from bottles at our small boutique resort,” he said. “In 2021 we’ll likely exceed 100 tons of sand. That’s a lot, but the average bunker contains about two tons of sand. With this program we have not had to buy bunker sand for the past five years.”

GARDENS AND BUTTERFLIES

In 2017, Audubon International developed Monarchs in the Rough, a program to restore an iconic American butterfly whose population has declined by 90 percent over the past two decades due to loss of habitat, disease and weather. The program has established more than 1,000 acres of new habitats at 720 facilities around the U.S., Canada and Mexico, including 24 courses in Southern California.

“When courses sign up for the program we send a supply of milkweed (food for the caterpillars) to the area for a one-acre plot of land,” said Alison Davy, office administrator. “You also need wildflowers since butterflies live off that nectar. Creating these habitats reduces mowing areas and provides support for other pollinators like hummingbirds, bees, and other animals. It makes the course more biodiverse pretty quickly.”

That’s what Brett Wininger, superintendent at Temecula Creek GC, hopes will happen. He and his team have built a new butterfly habitat adjacent to the ninth green on the Oaks course to go along with a small organic garden located right behind the first tee box on the layout.

“Both are to showcase what we’re trying to do here in terms of sustainability,” he said. “With the butterfly habitat, the goal is also to create an educational environment where people and elementary school kids can navigate through it and learn about caterpillars. It will also bring in other pollinators that will help with the garden (which provides food for Cork | Fire Kitchen at the Temecula Creek Inn).”

Over the past two years, Wininger has seen a mindset shift that he thinks may be related to the golf boom experienced during the pandemic.

“Instead of talking about how much water or land golf courses use, maybe people have gone out and actually played golf,” he said. “Now they’re realizing that being outdoors is so vital and that doing projects like these on a golf course can help balance things out. If you visit any course, you can come up with ideas to showcase things that create a positive profile. Every course has that opportunity.”

WHAT’S NEXT

The ever-changing requirements superintendents must juggle to do their job while affecting the environment in a positive manner pose plenty of challenges. But they can consult a thorough guide, thanks to the Golf Course Superintendents Association of America (GCSAA).

“One of the big things we did, back in 2015, was develop a ‘50 by 20’ initiative, which meant that by 2020, all 50 states would have a best-management practices guide,” said Jeff Jensen, field staff, GCSAA. “We reached that goal.”

The guide serves as a bible of sorts for sustainable golf course management from a maintenance standpoint. It covers everything from water management to pollinators to energy use and much more in its 250 pages.

Use of enhanced technology will continue to change the golf industry, according to Jensen.

“Fifteen years ago it was pretty rare for a superintendent to even have a handheld moisture meter,” he said. “Now more than 90 percent of courses across the country have those, and we’re starting to see the next step in ground-moisture sensors, which allow more efficient water use. Technology enhances the ability of supers to do their job better in a time of labor shortage.”

In the short term, that could mean autonomous mowers that weigh less, are easier on compaction issues and have GPS units that make them programmable to precise specifications. More electric and battery-operated equipment could translate into additional zero-emission opportunities, help reduce air pollution and noise, and provide a healthier work environment for employees. Solar power and clean energy could play key roles, while water conservation efforts — potentially in the form of onsite reclaimed water plants — could lead to healthier soils.

Jensen admits that there’s no silver bullet that addresses every single sustainability issue.

“It’s a lot of different efforts to use our natural resources properly and kind of become one with the land,” he said. “Golf courses recharge ground water, produce oxygen, cool the surrounding area, are good for carbon sequestration and are huge on wildlife habitats. Green space is disappearing, particularly in Southern California. We value that green space both for what it provides for golfers and for nature.