The Greatest Show on Earth: Reliving Tiger’s Miraculous 2008 U.S. Open Win

The 2008 U.S. Open was the embodiment of why sports as an entertainment vehicle often delivers as reliably as Amazon and more so than Hollywood studios. Its plot was inconceivable, as either fact or fiction, even while featuring golf’s leading man, Tiger Woods, from whom we had grown to expect the unexpected.

This, in a sense, rendered this Tiger’s finest performance in a career of memorable ones, not for its dominance or even its brilliance, but for how he transfixed us for nearly a week with agony and ecstasy and a victory so unlikely that it warrants its own wing on his sprawling legend.

The outcome came down to two: David and Goliath, as Eddie Merrins, the renowned “Little Pro” from Bel-Air CC, called them. Merrins was coaching the prohibitive underdog, Rocco Mediate, the parvenu who threatened to take down a giant on one of his favorite stages, the South Course at Torrey Pines.

We all know how it ended: Woods prevailed on the 19th playoff hole on a Monday afternoon. A sudden-death playoff for a national championship featuring one of the two greatest players in history cannot reasonably be called anti-climactic. But the defining moment of this U.S. Open — forever etched in memory and soon to be replayed endlessly in the run-up to another U.S. Open at Torrey Pines — came on the 18th green late on Sunday afternoon.

Woods had limped and grimaced his way to the finish line, the 72nd hole of the championship. A double stress fracture in his left tibia and a torn anterior cruciate ligament in his left knee that would require reconstructive surgery in the days ahead threatened all week to undermine his bid for a third U.S. Open victory and a 14th major championship.

THE OUTCOME CAME DOWN TO TWO, DAVID AND GOLIATH: AS EDDIE MERRINS, THE RENOWNED “LITTLE PRO” FROM BEL-AIR COUNTRY CLUB, CALLED THEM.”

Yet there he stood, broken but not beaten, staring down a birdie putt to tie Mediate and send the outcome to an 18-hole playoff on Monday. He was looking at 12 feet of peril, Torrey Pines’ poa annua, a grass notorious for getting bumpier as the day progressed. Factor in U.S. Open green speeds, a right-to-left path to the hole, and, well, fasten your seat belts. Turbulence ahead.

Woods explained his strategy on the putt, and in doing so introduced “Plinko” to golf’s vernacular. Plinko was the name of a game on the television show, “The Price is Right,” and it referred to the “plinking” sound” that a disc made as it bounded to and fro down a pegged board toward various monetary prizes.

“That was actually one of the worst parts of the green,” Woods said. “It’s so bumpy down there. And I just kept telling myself two-and-a-half balls outside the right, but make sure you stay committed to it, make a pure stroke and if it Plinkos in or Plinkos out it doesn’t matter, as long as I make a pure stroke.”

“That was actually one of the worst parts of the green,” Woods said. “It’s so bumpy down there. And I just kept telling myself two-and-a-half balls outside the right, but make sure you stay committed to it, make a pure stroke and if it Plinkos in or Plinkos out it doesn’t matter, as long as I make a pure stroke.”

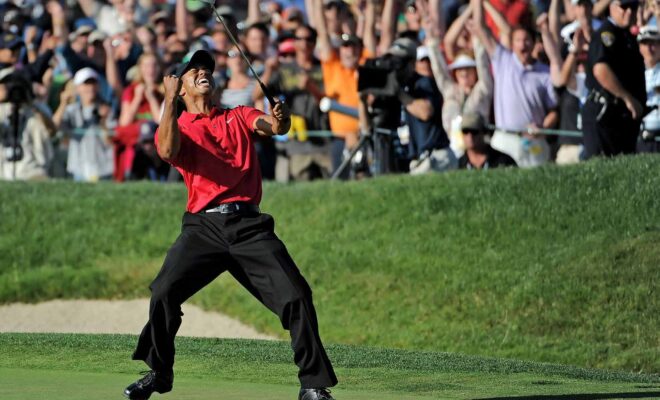

The large crowd framing the 18th green and lining much of the 18th fairway collectively held its breath, as viewers around the country no doubt were doing during this rare, edge-of-your-seat moment in golf. When Woods made his stroke, the ball began to trundle to the right of the target but at the last moment veered slightly left, enough to catch the edge of the hole and tumble into the cup. Woods’ trademark uppercut fist pump followed, as did roars so loud they might have been heard from Tijuana to Los Angeles.

“Expect anything different?” bellowed NBC’s Dan Hicks to the television audience, the answer obvious.

“I figured he was going to make it,” Mark Calcavecchia, watching at home, told ESPN’s Bob Harig a year later. “Bounced, hobbled, wobbled all the way down there. Went in. Could have lipped out. Curled right in there. It’s the legend of Tiger Woods.”

VALIDATING THE LEGEND

Yet to validate its status as legendary still required a victory in the 18-hole playoff the following day. Woods, notwithstanding his pain, took a 3-stroke lead through 10 holes, ostensibly eliminating the drama and replacing it with a foregone conclusion, though on a U.S. Open layout, with playoff pressure, there are no foregone conclusions. “Three shots on this golf course isn’t much,” Woods said.

The lead evaporated quickly. Consecutive bogeys for Woods and three straight birdies for Mediate gave the latter a 1-stroke lead through 15 holes. “I was playing a little military golf there. You know, left and right,” Woods said. “Roc just made three birdies right there in a row. And that hat trick was one of the more impressive runs that you can ever have on this golf course.”

The lead evaporated quickly. Consecutive bogeys for Woods and three straight birdies for Mediate gave the latter a 1-stroke lead through 15 holes. “I was playing a little military golf there. You know, left and right,” Woods said. “Roc just made three birdies right there in a row. And that hat trick was one of the more impressive runs that you can ever have on this golf course.”

Another 18th-hole birdie from Woods sent it to sudden death, starting at Torrey Pines’ par-4 seventh. And that’s where it ended, too, when Mediate hit his tee shot into a fairway bunker, hooked his second into a grandstand, took a drop, then failed to save par from there. He lost when Woods made a two-putt par.

A euphoric Tiger called it the greatest of his 14 major championships, “All things considered, yeah. I don’t know how it even got this far, but I’m very, very fortunate to have played 91 holes and then come out on top.”

The U.S. Open was his first start since he finished second in the Masters two months earlier. Two days after the Masters, he underwent arthroscopic knee surgery. Initially, he intended to play the Memorial as a tune-up for the U.S. Open, but his plans were derailed when it was discovered he had two stress fractures in his leg. He could not play the Memorial and doctors advised him not to play the U.S. Open, either.

But this was a major championship and this was Torrey Pines. The combination of the two was too enticing for a famously stubborn golfer who lived for majors and was a fixture in Torrey Pines’ winner’s circles. Earlier in the year there, Woods won what then was called the Buick Invitational for the fourth straight year and the sixth time overall. He also won a Junior World Championship there.

“This course has been really kind to me,” he said following his January victory. “Ever since junior golf, all the way through my professional ranks, I somehow really seemed to have played well here. It fits my eye. I feel very comfortable here.”

“This course has been really kind to me,” he said following his January victory. “Ever since junior golf, all the way through my professional ranks, I somehow really seemed to have played well here. It fits my eye. I feel very comfortable here.”

Yet when June came, discomfort prevailed, though to what degree was not yet known. A few days before the Open began, he was typically reticent in addressing his health concerns, as though they no longer were a factor. Once play began his body language revealed more than he had, though again he declined to elaborate, as his post-round interview on Thursday demonstrated.

Question: Was the knee bothering you during the round?

Answer: It’s a little sore.

Question: Did that affect how you were playing? Did you have to hold back?

Answer: I just go play.

Question: Are you taking anything for the pain?

Answer: Oh, yeah.

Question: Will you do any ice rehab, whirlpool afterwards?

Answer: Um-hum.

At times on the course he nearly fell to the ground after hitting tee shots and often appeared to be in excruciating pain, though some might have concluded that it was performance art. Woods had developed a reputation, at least among caddies, true or not, of dramatizing the extent of his injuries. Four years earlier, the Associated Press reported that “some of the caddies privately called him ‘Oscar’ for his dramatic performance.” Adam Scott, Woods’ playing partner in the first two rounds at Torrey Pines, was among the skeptical.

“Tiger, back then, because he beat us all the time, we didn’t like him that much,” Scott told reporters a year later. “The skeptic in me said he’s a great showman. Even when he was playing great golf back in the day, he was milking everything to his advantage. The skeptic in me thought he was putting it on a bit, but I really don’t know the extent that his leg was damaged. He thought he was good enough to play and he won. He knew what he was doing. He got it around somehow.”

The injuries were real, and apparently the pain was, too. Woods would not play again until the following February. Only Tiger’s golf was Oscar-worthy, a performance that was memorably great theater sans theatrics, and for one special week, at least, was the greatest show on earth.