The Industry at Mid-Decade: The Good News is that the Bad News isn’t All That Bad

Figures don’t lie. But they don’t tell the whole truth either. The whole truth requires context, and nowhere does this principle apply more than in the way the golf industry has dealt with the steady drumbeat of bad news about the health of the game. More accurately, the way the industry has been wallowing in that news.

We know the numbers, and the numbers aren’t good. There aren’t as many golfers as there were a decade ago. Despite the dedication of so much energy and so many resources to junior golf development, there are fewer junior golfers in America today than a decade ago. Aggressive discounting has become the norm in the daily fee market and is fast becoming a way of life in the municipal market. Golf clubs of all stripes are smaller than they used to be, and a number of private clubs have ample exit lists. We can’t remember the last time a golf course opened, but we can certainly recall a bevy of recent closures. Throw in a series of severe droughts, a tighter regulatory noose and geometrically increasing costs of water and energy – and it’s easy to wallow.

It’s become even easier to lose confidence in the fundamental allure of the game and start questioning whether the rhythms of modern American life still provide fertile ground for a game that is inherently expensive, deliberate, traditional and difficult. That loss of confidence has caused many to take a serious look at 15-inch holes, 12-hole courses, alternative Rules, dual equipment standards and other such “blasphemies” as solutions to attracting lost generations and demographics to the game.

Taking second looks at whether yesterday’s traditionalisms have devolved into anachronisms always makes good sense. Ceasing and desisting from doing stupid things makes equally good sense. But before the game throws the baby out with some of this dirty bathwater, it also makes sense to take a second look at whether we have been interpreting events and numbers accurately.

My “second look” informs me that we just might be overreacting.

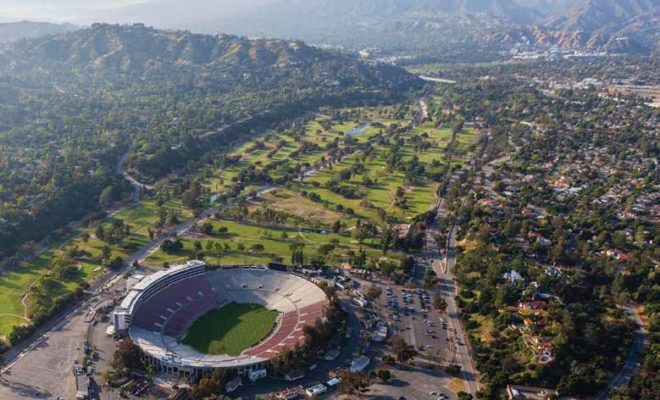

Literally from the moment the shooting stopped after World II until early in the 21st Century golf enjoyed an unprecedented run of success. For 59 consecutive years from 1946 through 2004 there were more golf courses in America on December 31 of each of those years than on January 1. Through wars, recessions, double dip recessions, threats of thermonuclear war, hyper-inflations, gas lines, domestic unrest, constitutional crises, malaises and all other sorts of dislocations one thing remained constant: Golf grew. Sometimes it grew faster, sometimes slower – but it grew.

As with any such consistent run of success, the golf industry thought the good times would roll on forever, leading to a particularly robust run of construction at the tail end of the 59-year expansion. The ancient Greeks called it hubris; a certain Federal Reserve Chairman called it “irrational exuberance.” Call it what you want, but that is what human beings always seem to do; golfers are no exception.

By 2005 the golf industry was long overdue for a market correction. And the market began to “correct.” Golf courses built in the 1990s on business models requiring an ever increasing supply of golfers willing and able to remit triple digit greens fees began to struggle as supply outran demand. Adding to the problem were hundreds if not thousands of golf courses that were constructed predicated not upon selling memberships or greens fees, but upon selling the condos and houses that surrounded them, often leaving an unsustainable golf course/club once all the real estate was sold. And what was the sector whose bubble burst and led America in 2008 into its deepest recession since the 1930s?

Two intersecting market correction forces conspired in 2008 to triple down on the overdue golf market correction. The fact that the industry has just begun to see some green shoots sprouting from the dry ground created thereby is indicative of nothing more than the reality that it does take time to rebound from the confluence of two bursting bubbles. It is not necessarily indicative of a game no longer in sync with modernity or a game no longer appealing to a swath of the population large enough to sustain its ambitions.

There is virtue in adversity. That is the additional silver lining in this sad scenario. The golf industry has emerged from these dry years chastened and humbled, leaner and meaner, allied and organized – in short, prepared to lead the game into another period of growth, albeit perhaps not as robust or sustained as the Halcyon days of 1946-2004.