SoCal’s Course Designers: A Home Team Worth Rooting For

SoCal is blessed with a wide variety of golf courses, ranging from the deserts to the mountains to the ocean. The architects who designed our layouts are likewise a varied group, with most of the greats of course design represented. We may not have a Donald Ross of which to boast, but Alister Mackenzie, George C. Thomas, Billy Bell Sr. and Jr., Jack Nicklaus, Tom Fazio, Tom Doak … and so many others have contributed so greatly to our enjoyment of the game through their acclaimed works. So too have those architects who nowadays call SoCal home, because as you’ll read on the following pages, the home team is both prolific and formidable.

CARY BICKLER

Celebrating 50 years as golf course architect in 2018, San Diego-based Cary Bickler has seen it all, through peak times and economic downturns to varying trends in design styles. But he still loves his chosen profession, one in which he started unofficially working when he was just 14 years old.

Celebrating 50 years as golf course architect in 2018, San Diego-based Cary Bickler has seen it all, through peak times and economic downturns to varying trends in design styles. But he still loves his chosen profession, one in which he started unofficially working when he was just 14 years old.

That’s when his family decided to get into the golf business, hiring Lawrence Hughes to build 18 holes at Green River Golf Club in Corona, on land overlapping Orange and Riverside counties.

“In the summer of 1957, I was part of construction crew there running a skip loader and doing whatever they told me to do,” he says. “It was pretty cool when you’re that young to run a piece of equipment.” That experience led to an apprenticeship with Hughes (an apprentice himself of Donald Ross), and after playing golf and studying art at San Diego State, Bickler started his own course design firm.

After designing a second 18-hole course at Green River Golf Club, he soon gravitated to restoration and renovation projects. “Not everybody wanted to show up and do a couple of bunkers or one green, but I would do that,” he says. “Nowadays I’m pretty sure everyone would show up to do that.”

It wasn’t an easy path. “I did it the hard way, dug my heels in, and made a name for myself,” Bickler says. “I had opportunities to join firms, but I felt I could do it on my own. That’s the way it worked for me and I’m glad I did it that way. I think I learned it from the entrepreneurship and style of my father. He would develop ideas on his own and surround himself with good team players. I did the same thing.”

His course portfolio includes original designs at Encinitas Ranch (“It’s the only course I know of that had to cut back the number of rounds being played.”), Shandin Hills Golf Club in San Bernardino, The Loma Club in San Diego, The Country Club at Borrego Springs and Hawks Landing Golf Club at Blue Skies in Yucca Valley. His renovation projects have included work at La Cumbre Country Club in Santa Barbara, La Jolla Country Club, Mesa Verde Country Club in Costa Mesa, Camp Pendleton Marine Memorial Golf Course and San Diego Country Club.

“There have always been booms and busts, but the renovation and restoration of existing courses has been a constant necessity,” he says. “Fortunately, I got my start by focusing on that type of work and it has continued to be the foundation of my business model. And that seems to be the thrust of the current marketplace demand.”

He has also seen the business go from an explosion of building new courses (1980s and ’90s) to a more respectful preservation of Golden Era (roughly 1910 to 1940) designs. “We’re also being better stewards of water use now and addressing the need for faster play,” he says. “The other big change is moving from who could make the biggest, hardest course on the planet to getting back to looking at courses that work well, like ones where you leave the green and can easily find the next tee in a hurry.”

A proud Southern California native, Bickler never gave thought to basing his business elsewhere. “I love the ocean and the weather, and my wife loves the palm trees,” he says. “I grew up here and have a lot of friends in the area. I have worked out of state, but I’ve been fortunate to spend my whole career right here in Southern California.”

Even after a half century in the golf architecture business, the 74-year-old Bickler has no plans to slow down. “I don’t ever see myself stopping,” he says. “I really enjoy it.”

TODD ECKENRODE

Todd Eckenrode had no idea at the time what effect growing up playing Pasatiempo Golf Club would have on his life. But ultimately, his days spent walking the fairways of the classic Alister Mackenzie layout in Santa Cruz would have a profound impact on a young golfer who would one day become one of Southern California’s most prominent golf course architects.

Todd Eckenrode had no idea at the time what effect growing up playing Pasatiempo Golf Club would have on his life. But ultimately, his days spent walking the fairways of the classic Alister Mackenzie layout in Santa Cruz would have a profound impact on a young golfer who would one day become one of Southern California’s most prominent golf course architects.

Eckenrode, who started Origins Golf Design with partner Charles Davison in 2000, has a resume filled with a wide variety of award-winning creations and restorations that often can trace their DNA back to the Golden Age of course design.

“I was very fortunate,” Eckenrode says of his high school days working at and playing Pasatiempo. “I didn’t know it then, but it really influenced my appreciation of old-style design, the lay-of-the-land style before the days of bulldozers. It’s probably no coincidence the majority of clubs we work for are built in that era.”

Eckenrode’s renovation of Lakeside Country Club was Golf Inc. magazine’s private course renovation of the year for 2018. It was the third time in four years he has earned that distinction, added to his work at Brentwood Country Club in 2015 and Virginia Country Club in 2016.

Of course, he doesn’t restrict his work to courses built a century ago. He’s currently working on a renovation at El Niguel Country Club, where a creek running through the course offers intriguing sight lines and natural design elements that encourage thoughtful play.

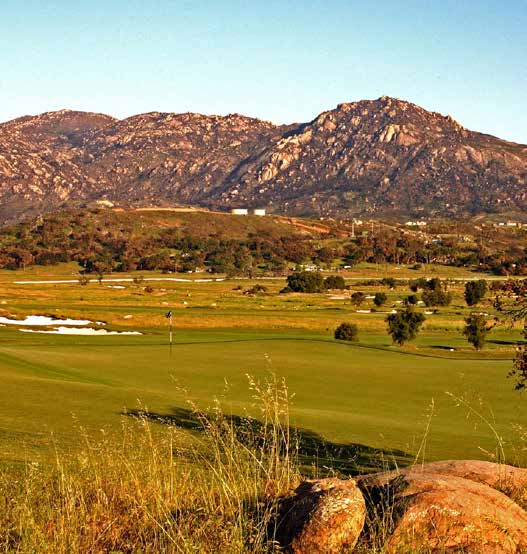

His original designs have been equally praised. Barona Creek Golf Club near San Diego is a regular on lists of top public and casino courses, and the Links at Terranea in Palos Verdes is a stellar nine-hole design on a bluff overlooking the Pacific that was designed to accommodate resort players.

At Borona, Eckenrode used the distinctive natural features — the hilly terrain and stately California oaks — to create a course with the variety that he considers so important to design. Terranea was a different challenge.

“It was so much fun,” he says. “We had never done nine par 3s before. Figuring out how to make the holes all different, that was a real challenge. Obviously, the site was spectacular, but we tried to orient holes for the best sight lines down the coast.”

As new construction of courses slows in this country, many architects, including Eckenrode, are doing more restorative than original work.

“There’s certainly more freedom and creativity in new projects,” he says. “But I have such an interest in and respect for old courses, they are really engaging as well.”

CAL OLSON

It wasn’t until he was 39 years old that Cal Olson realized his true calling was to design golf courses. A landscape architect and civil engineer, he decided that blending those talents would work nicely to create spaces where people could enjoy themselves while steering a small ball around trees and over wandering streams on the way to nicely manicured greens.

It wasn’t until he was 39 years old that Cal Olson realized his true calling was to design golf courses. A landscape architect and civil engineer, he decided that blending those talents would work nicely to create spaces where people could enjoy themselves while steering a small ball around trees and over wandering streams on the way to nicely manicured greens.

“It hit me while I was doing a few things in the desert,” Olson says. “I didn’t really know anything about it, but I learned it through osmosis, being around architects.”

Little did he know back in 1980 that Cal Olson Golf Architecture, based in Laguna Niguel, would stamp its mark not only on Southern California golf, but expand to countries all over the world.

His redesign of Skylinks Golf Course in Long Beach was named the best public redesign of 2004 by Golf Inc. He carved Sierra Star Golf Course out of the forest at Mammoth Lakes, a lengthy project that required trucking in enough topsoil to grow turf atop the rocky, mountainous terrain.

With Payne Stewart brought in as his high-profile partner, he designed Coyote Hills Golf Course among the working oil rigs, rugged terrain and environmentally protected habitat in Fullerton. That project required a $50 million soil cleanup by Unocal that took about 10 years before Olson could begin weaving his fairways around the 23 remaining wells, miles of pipelines and protected gnatcatcher habitat.

“That was a lengthy project but really fun,” he says. “I learned a lot about oil, and gnatcatchers, and got to know Payne Stewart.”

But perhaps his favorite project has been the ultra-exclusive Algarov Estates Golf Club in Moscow, a $50 million project framed by multimillion-dollar homes not much smaller than the Kremlin and just as lavish.

“That was extremely interesting,” Olson says. “Our client there didn’t want to consider budget. We imported mature trees from thousands of miles away. Going to Russia on and off for six years, that was a once-in-a-lifetime gig.”

CASEY O’CALLAGHAN

Casey O’Callaghan’s philosophy of course design is really pretty simple: “I suppose if I have one, it’s to create beautiful golf courses that are fun to play,” says the Newport Beach architect who has renovated scores of Southern California courses, from city-owned municipal layouts to high-end private clubs.

Casey O’Callaghan’s philosophy of course design is really pretty simple: “I suppose if I have one, it’s to create beautiful golf courses that are fun to play,” says the Newport Beach architect who has renovated scores of Southern California courses, from city-owned municipal layouts to high-end private clubs.

It’s probably not surprising, then, that the owners of Industry Hills Golf Club turned to O’Callaghan in 2005 to renovate the Eisenhower and Zaharias courses, two layouts known as much for their diabolically penal nature as their interesting routing.

His work on the Ike was one of Golf Digest’s top five renovations of the year.

“Our intention was to make it more friendly and forgiving,” he says. “There are some courses that just kick you in the teeth, you play once and don’t want to go back.”

O’Callaghan, who graduated from UC Berkeley after studying environmental design and architecture, worked with Cal Olson (1990-’93) before heading out on his own. His first original project was Hidden Valley Golf Club in Norco.

“It was really challenging,” O’Callaghan says, “with huge elevation changes, large boulders; we moved 700,000 yards of dirt, but there were some huge rocks we weren’t going to move. It was fascinating being out there.”

He followed that with the highly regarded Arroyo Trabucco Golf Club in Mission Viejo, working with PGA Tour veteran Tom Lehman. That was selected one of the top-10 new public-access courses of 2004 by Travel & Leisure Golf magazine. And O’Callaghan, with Amy Alcott consulting, designed the South Course at Indian Canyons Golf Resort in Palm Springs. That one was rated No. 28 in the country by Golf Digest for Women.

“The land was flat, and there had been a course there but it had gone fallow,” O’Callaghan says of the Indian Canyons project. “They wanted a beautiful course where people could score and want to come back. It took some creativity.”

O’Callaghan recently began a complete bunker renovation of Friendly Hills Country Club in Whittier.

“We’ll give an identity to the bunker renovation, make them so players can get in and out of them and recover from them,” O’Callaghan says. “When you do an 18-hole bunker renovation, you can really touch some aesthetics there. It’s going to be dynamite.”

AMY ALCOTT

Amy Alcott kept her eyes open throughout her Hall of Fame playing career on the LPGA Tour. While winning 29 events, including five majors, from 1975 to 1991, she made notes of the design elements that she liked on golf courses around the world. An interesting bunker complex, a demanding-but-fair dogleg, a rolling parkland layout winding through mature pines and hardwoods.

Amy Alcott kept her eyes open throughout her Hall of Fame playing career on the LPGA Tour. While winning 29 events, including five majors, from 1975 to 1991, she made notes of the design elements that she liked on golf courses around the world. An interesting bunker complex, a demanding-but-fair dogleg, a rolling parkland layout winding through mature pines and hardwoods.

“I pretty much always enjoyed the wow factor in golf,” says the Santa Monica native whose jump into Poppie’s Pond after winning her third Nabisco Dinah Shore title started one of the LPGA’s lasting celebratory traditions.

“I was always interested in design, and wherever I’d play — Manila, Cleveland, Tokyo, wherever — I’d remember what holes looked like, what courses were special.”

Alcott is a strong believer in the Tee It Forward PGA/USGA concept that encourages all players, regardless of gender, to hit from tee markers that fit their driving distance. Her main design accomplishment to date may be her contributions to the Rio de Janeiro course used in the 2016 Brazil Summer Olympics. She was a consultant with noted architect Gil Hanse and left her mark, perhaps most notably in helping design the short par-four 16th hole.

“We shortened it to about 340 yards with OB dead to your left,” she says, “so you’d have to hit a great drive or a 5-iron short. It was a real risk-reward near the end of a round. I really like short par 4s … where you can made a 3 or a 6. It’s one of the things on that course I was proudest of.”

Alcott also worked with Newport Beach designer Casey O’Callaghan in the building of Indian Canyons Golf Resort in Palm Springs, and with Hanse on a remodel of Ridgewood Country Club in New Jersey.

“As a player, you know what makes a good hole, but you don’t know the nuances about how bunkers are designed, about grasses, drainage,” Alcott says. “For me, it was easy to be a Hall of Fame golfer and think you know it all about design, but I’m still a rookie, learning. Still, I think I’m pretty good.”

GEOFF SHACKELFORD

When Geoff Shackelford’s father joined Riviera Country Club, the then-16-year-old had no way of knowing how that decision would impact his life and career. But playing the famous course, and learning about George C. Thomas (who designed it with Billy Bell), sparked his interest in golf course architecture.

When Geoff Shackelford’s father joined Riviera Country Club, the then-16-year-old had no way of knowing how that decision would impact his life and career. But playing the famous course, and learning about George C. Thomas (who designed it with Billy Bell), sparked his interest in golf course architecture.

Three decades later he has an original course co-design (Rustic Canyon in Moorpark, with Gil Hanse), a high profile restoration project (the North Course at Los Angeles Country Club, again with Hanse), and consulting work at Woodland Hills Country Club and La Cumbre Country Club in Santa Barbara to his credit.

But it was economic reality that turned the now 46-year-old into a golf media mainstay and sought-after expert on golf course architecture. He’s the author of 11 books (including a biography of Thomas and a club history of Riviera), owner of an eponymous, golf-centric website; writer for Golfweek; contributor on Golf Channel; and co-host of The Ringer’s ShackHouse podcast.

“When the market collapsed in 2008, it became clear to me that to try and make a living off course design was going to be tough,” says the Pepperdine University graduate. “I’ve always enjoyed the media side of my work. I didn’t want to give that up. I think it’s more interesting to be involved in a variety of things. I’ve been pretty good at adapting to what the next medium is.”

Shackelford, who names LACC, Wilshire Country Club and Santa Anita Golf Course as examples of what he calls great course designs, uses three basic questions as his barometer for judging the architectural quality of a course. “Would I want to play this course every day?” he says. “Can I remember every hole after playing it? Would I take my dog for a walk on the course? That last one speaks to the scale and sensibility of the place. Is it just a nice place to go for a walk?”

While he’s not sure if further course designs will be part of his immediate future, Shackelford will always have the project at LACC as a career highlight. “To work with Gil Hanse on restoring George Thomas’ design of the North Course was the privilege of a lifetime,” he says. “You get to put something that spectacular back in place, well it was highly rewarding. But it also sets a bar that’s tough to attain again.”