Par for the Course

Par: In the U.S., it’s golf’s most bandied-about concept. The funny thing is, it really has no place in the game, at least not within the framework of the rules that govern golf. How could that possibly be?

“Par is an artificial construct.”

That blasphemer is Arthur Little, a former course owner, avid golfer and industry consultant who has recently done some insightful work on the reality of how far golfers of every ilk hit the ball, as we’ve discussed in previous columns.

We obsess with par, the relation of our scores to par, because we think “par” is the very fabric of the game. We feel elated, even validated when we kick par in the teeth, we question our place in the cosmos when par has roughed us up. But it’s really no more than a rogue thread, not the existential weave.

THE MEANING OF PAR

The USGA doesn’t really bother itself with par, which might get some expelling single malt through their nostrils when thinking back to U.S. Opens presided over by grim-faced men in blazers manning the bulwarks as if Lady Liberty herself, as opposed to some arbitrary number, was being defiled. For its part, the keeper of the keep here in the good old U.S. of A never defined “par” in the Rules of Golf.

Par does have a meaning, it’s just not a ruling principle as with where to peg the tee shot in relation to the markers, anchoring or how many clubs are in the bag. More importantly, par has little bearing on how we quantify our abilities as players.

Per the USGA Handicap System Manual: “‘Par’ is the score that a scratch golfer would be expected to make for a typical hole. Par means expert play under ordinary conditions, allowing two strokes on the putting green. Par is not a significant factor in either the USGA Handicap System or USGA Course Rating System.” [Emphasis added.]

If that’s confusing, you’re not alone. Most of us who call ourselves golfers don’t even maintain a handicap, and many who do might not fully understand what to do with it.

If par is structurally no more than so many 3s, 4s and 5s that add up to 71 or 72 or something around there, and we shouldn’t measure ourselves in relation to it because it, well, really has no bearing on the metric of how well we play, then why are we so fixated on the concept?

Quite frankly, in its starring role, it makes watching a stroke-play event more easily digestible. In a tournament, where absolute position is not determined until the last putt drops, speaking to where a player is in relation to par allows us to track who is in the “lead” at that particular point in time regardless how far along he or she is in the routing, hence the phrases “clubhouse leader” and “leader on the course” late on Sunday afternoons.

There has to be more, there just has to be.

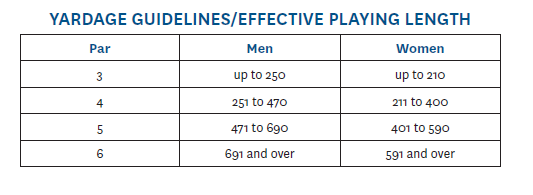

Let’s look to the USGA again. The ruling authority specifies “effective playing length” for determining par of a particular hole for a scratch player. Referring to the graphic that follows, let’s take a par 4, which should play at 251-470 yards for a man and 211-400 yards for a woman. Those are ranges with which we’re all familiar. Why then did Erin Hills have multiple 500-plus-yard par 4s?

The ironic thing about this longest major championship course in history is that it should have been set up even longer when seen from the perspective of equity, which is what most of us think these notions of par and handicap, playing in relation to some standard, is all about.

A “LITTLE” ADJUSTMENT

A “LITTLE” ADJUSTMENT

In a larger sense, this yardage creep — sometimes yardage leap — is not a good thing for the game, overall. Too many developers, course owners, recreational players and competition-committee members see “longer” and “tougher” and come down with an acute case of Pavlovian salivation, and then up go land acquisition, construction and maintenance costs, up go dues and green fees, and down go pace of play and enjoyment. It works for Augusta National, not our clubs.

By Arthur Little’s estimate, par-72 Erin Hills should have played anywhere from 8,300 to 9,000 yards, not just short of 7,800. That’s what it would take for these truly elite athletes to “play equal shots as we’d be playing on a 6,000-whatever yard course.” And by equal shots he means approach shots.

Equity in golf does not come from disparate players hitting their drives to about the same spot. That’s how we’ve historically done it, moving “lesser” players forward so drives end up in the same general vicinity downrange, give or take 20 or 30 yards, which is meaningless in most applications. If we are to equitably allow competition across skill sets, then we need to position tees according to how far players hit every club in the bag. If the stick has a wedge in her hand for the second shot on a par 4 then her short-hitting hubby should as well.

According to USGA-provided data stemming from Little’s research and analysis, if a high-swing-speed player is to have a short-iron in hand for a par 4 approach, the tee should be at 470 yards. For the average recreational player to have the same club in hand for the approach, the hole must be shortened at least 100 yards.

As Average Joe hits both his driver and his short-iron a lesser distance than the better player, he needs a yardage concession both off the tee and in the fairway. If that’s a slow-swing-speed player, the hole needs to be half as long as the stick’s. Ask yourself, as a white-tee player (and most of us need to be there), how often do you see 100, 120, 140 more yards between that spot and where your friend the 3-‘cap is standing? Exactly.

Little’s mantra is simple and sensible: “If tees are positioned in such a way that people are playing based on swing speed, then par will again gain relevance as those players are getting a chance to get to greens in regulation.”

I’m not sure about all of you, but around here, scorecard and starter admonitions as to tee selection are based on handicap, not swing speed.

The USGA points out that while there is nothing like a specific “hole rating” within the handicap and course rating systems, if we look into the mad math of it all we’d see that a particular par 4 might play as a 3.8 for the scratch player and a 4.6 for a bogey golfer. With this allowance, respective abilities are being weighted, but is it to the extent as might be warranted based on the significant through-the-bag yardage differentials Little highlights?

Little is convinced that how far we hit the ball, through the bag, needs to move front and center if and when a new system of computing how it is we are catalogued as players is devised, and in doing so par will be relevant to each of us. His proposal envisions seven sets of tees “rated” by driver swing speed, from 110-plus MPH to sub-60 MPH.

“Anytime a player is playing a set of tees that is too long for his or her swing speed, both the course rating (which is based almost completely on length) and the slope (length is still the predominant factor) are too low,” he says. “If tees were ‘rated’ and ‘sloped’ for swing speed … players would play the set of tees that ‘fit’ their game. There would be no need for men’s/women’s ratings/slopes.”

As we presently step to the tee, the blue/white/red paradigm doesn’t hit the sweet spot, and a slower-swing-speed player being handicapped off a typical shortest-tees-offered layout of 5,600 yards or even 5,000 yards is still taking on too much course, by Little’s system, so how accurate or fair is that index that he or she is carrying around?

Little admits the concept is an “ideal-world” scenario. He is also a friend of and sought-out advisor to the ruling authorities

Golf has changed in recent years. In context it can almost be said that strange things are happening, particularly in light of the previous pace of regulatory evolution. If high-temple standards on drops and hazards and how we comport ourselves on the green are on the chopping block, maybe notions on tee selection, that nebulous but all-encompassing concept of par, the handicap system, itself, might not be sacrosanct?

Perhaps we can look forward to a little more help from our friends from Far Hills.