Ojai Valley Inn & Spa: Elegance, Grace & Lots Of History

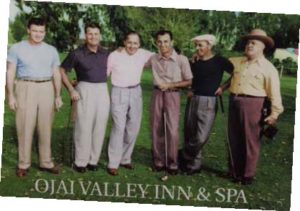

You know you’re in classic territory as soon as you grab your Ojai Valley Inn & Spa scorecard and squint at its cover photo. Who are those gents with the Brylcreemed hair, sporting vintage pleated chinos … familiar faces that you probably can’t quite recall?

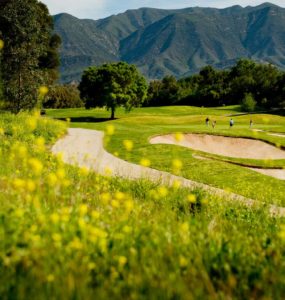

Ask any course employee and they’ll gladly fill you in, because everyone loves to talk history here. Pride in the past is abundantly clear at this George Thomas–designed course that dates back to 1923. Echoes of yesteryear are everywhere, starting with Thomas’s remarkable design, which he created in the rugged, oak-studded Ojai hills without today’s landscape-sculpting mega machinery. Instead, he worked with the existing contours of the land, imbuing the course with twists and turns and creative touches that are at once fascinating and confounding.

Take No. 2, for example, among GOLF Magazine’s 500 greatest golf holes — a 358-yard downhill par 4. Your drive has to clear a rugged barranca to reach the fairway, and don’t even think about aiming for the green. You can’t see it anyway; it’s well hidden (and guarded) by a copse of Ojai’s signature oak trees. The play is like a knight’s move in chess, an L-shaped approach, straight over the barranca (you hope), then hang a right. Now it’s a straight shot toward the … uh, well, not exactly. The hole lies beyond another barranca. But those oak trees sure are pretty. And just how do you get over the barrancas? Thomas designed a couple of lovely bridges. Fiendishly creative, this hole is named Devil’s Cauldron.

“You have to play the course the way Thomas designed it,” says Ojai’s director of golf, Mark Greenslit. “You can’t overpower it. You have to lay up where you’re supposed to.”

Big hitters suddenly find they’re trapped in the 1920s, and that’s part of the delight of playing this course. You can flex your biceps on some holes — particularly the back 9 — but Ojai doesn’t really favor one type of golfer over another.

Ojai Country Club was the creation of Edward Libbey, a glass magnate from Ohio whose wealth, vision and benevolence are on display throughout the town of Ojai. (He underwrote such community landmarks as the downtown arcade, post office and city park.) Libbey came to the valley in 1916, was enchanted by its beauty and serenity (who isn’t?), acquired some land and began to develop what amounted to a master-planned community.

Ojai Country Club was the creation of Edward Libbey, a glass magnate from Ohio whose wealth, vision and benevolence are on display throughout the town of Ojai. (He underwrote such community landmarks as the downtown arcade, post office and city park.) Libbey came to the valley in 1916, was enchanted by its beauty and serenity (who isn’t?), acquired some land and began to develop what amounted to a master-planned community.

Like any viable real estate venture, it needed a country club. Libbey enlisted Thomas to build the course and Wallace Neff to design the Spanish Colonial Revival clubhouse — the architectural motif that defines the resort to this day. The first guest rooms came a decade later, but carried forward Neff’s motif, most notably the red tiled roofs. That original wing, known as the Wallace Neff Building, houses a hallway filled with memorabilia — a must-see for any fan of the legendary course.

Thomas harmonized his design to suit the hilly landscape, and to frame stunning views of the surrounding mountains — views that have changed little in the ensuing years. So what did the architect himself think of his Ojai creation? Thomas, whose quiver includes Bel-Air CC, Riviera CC, and Saticoy CC, among other SoCal gems, said, “I consider the Ojai course as far and away above the best of them. There is not a weak hole at Ojai.”

War Years, Hollywood Links

Ojai Country Club went dormant during World War II, when it became the site of a military training base called Camp Oak. Tents pitched on the fairways housed a battalion of a thousand soldiers, while officers billeted in the clubhouse. The camp was also used for rest and recuperation, and the likes of Bob Hope and Bing Crosby came to perform for the gathered troops. During the war years, the army plowed over two holes that weren’t restored when the course reverted to private ownership. (More about the Lost Holes in a moment.)

After the war, Ojai became a place of glitz and glamor. Loretta Young and Irene Dunne were investors. George Cukor filmed Pat and Mike, starring Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy, in Ojai, which was already famous as the Shangri-La depicted in Frank Capra’s 1937 Lost Horizon. Ronald and Nancy Reagan were frequent guests. Fred MacMurray and June Haver were married in a fairway cottage. In 1990, Jack Nicholson filmed scenes for The Two Jakes, a Chinatown sequel, at the course.

After the war, Ojai became a place of glitz and glamor. Loretta Young and Irene Dunne were investors. George Cukor filmed Pat and Mike, starring Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy, in Ojai, which was already famous as the Shangri-La depicted in Frank Capra’s 1937 Lost Horizon. Ronald and Nancy Reagan were frequent guests. Fred MacMurray and June Haver were married in a fairway cottage. In 1990, Jack Nicholson filmed scenes for The Two Jakes, a Chinatown sequel, at the course.

In the 1950s, pro Jimmy Demaret became the face of the Ojai course, a fitting choice for a flamboyant golfer who held his own in the Hollywood hobnobbing department. (But let us not forget that Demaret won three Masters and 31 TOUR events.) Demaret frequently played with his pal Ben Hogan during those years. Doug Sanders took over as club pro in the 1960s.

Still today, actors (and avid golfers) such as Malcolm McDowell and Bruce McGill make Ojai Valley their home.

Senior Tour Legacy

Like any true classic course, Ojai has seen its share of great golf and memorable tournaments. In the late 1980s through the 1990s, Ojai gained national renown when it hosted seven Senior PGA Tour (now the Champions Tour) events. Winners included Chi Chi Rodriguez, Bruce Crampton, Bruce Devlin and Al “Mr. 59” Geiberger. Arnold Palmer played all six events. It was during one of those tournaments, the 1995 FHP Health Care Classic, that Buddy Allin set the course record — a scorching 61. No, he didn’t win the event.

The year Devlin won, 1993, was memorable for a torrential downpour that so soaked the course that only two holes, back-to-back par 3s, remained playable (once the greens were squeegeed) for Devlin’s playoff with Dave Eichelberger. As the rain continued to fall, the stage was set for an eternal back-and-forth scenario — but Devlin pulled off his victory after just two holes.

The course also hosted made-for-TV events — the NBC Golf Skills Challenge — in 1997 (won by Billy Andrade) and 1998, when Nick Price edged Casey Martin on the last hole.

Lost and Found

Although Ojai is decidedly a George Thomas course, it’s seen some modifications over the years. A 1988 remodeling by Jay Morrish toughened it somewhat while retaining its traditional challenges. It was then that the front and back nines were reversed. The front nine is charming, enchanting, almost intimate. It includes the aforementioned No. 2, followed by a hole called Shorty — all of 115 yards from an elevated tee, Thomas’s shortest hole ever. Piece of cake? Hardly. A tee shot long or to the right puts you in dire straits. Play short? No. Rough or barranca and an uphill pitch there. If you can find your ball. The solution: Hit the heart of the green. Simple.

The back nice holes build in difficulty and include the course’s toughest par at 18. Here too are the most spectacular views. No. 11 is called Pink Moment in honor of the famous Ojai phenomenon — a glorious wash of alpenglow that paints the sandstone face of Topa Topa Mountain pink around the time of sunset.

The back nice holes build in difficulty and include the course’s toughest par at 18. Here too are the most spectacular views. No. 11 is called Pink Moment in honor of the famous Ojai phenomenon — a glorious wash of alpenglow that paints the sandstone face of Topa Topa Mountain pink around the time of sunset.

The back nine is also the site of those Lost Holes that got plowed under during the Second World War. The holes, 16 and 17, were only restored in 1999. With some encouragement from Ben Crenshaw, Greenslit enlisted Carter Moorish, Jay’s son, to restore the holes, working from an old scorecard and a photo proffered by a local historian.

The resulting holes are so memorable that it’s hard now to imagine the course without them. The 16th is named Captain’s Pride (“Captain” was Thomas’s nickname), and it does its original designer proud. The 203-yard par 3 with an elevated tee is guarded by a daunting foreground maze of bunkers and dense oaks left and right. Once again, the solution is simple. Do the Captain proud. Just hit a perfect shot.

Ah, yes. That scorecard photo. From left to right: Al Demaret, Jimmy Demaret, Jack Benny, Ben Hogan, George Fazio and legendary golf journalist Scotty Chisholm.

Again, classic.