Perdition, Hope and Great Big Bertha

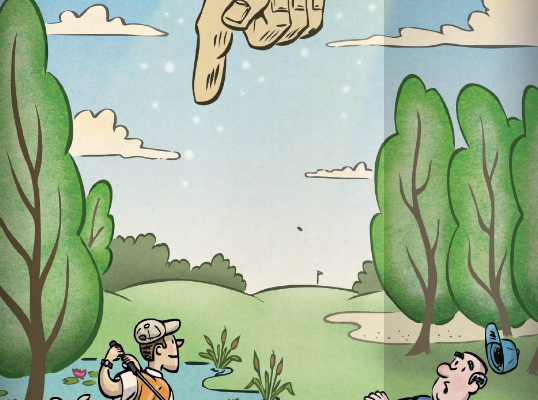

The Golf Gods come straight outta the Old Testament, imposing fire, brimstone and shanks. A polytheistic group, their ranks include tricksters and sirens, prone to drop a rare long putt simply to ensure continued play and consequent suffering. And they grow particularly cruel when age starts turning every par 4 into driver, three-wood and wedge.

Indeed, a friend in his late 70s plays the exact same series of shots over 18 holes, with only a few yards variance, five days a week. He seems not to notice the crushing redundancy, but it’s like Bill Murray in Groundhog Day, perdition on earth. It’s also an alarming foreshadowing, as the years creep into my fade-plagued game.

This past summer, however, breathless ads appeared in the major golf magazines. Callaway was introducing a new Great Big Bertha, putting their best new technologies into a name that galvanized amateur golf precisely 20 years ago. “Great Big Bertha Returns to Leave No Yard Behind,” proclaimed the copy. “Our fastest face, most advanced, yet simple, adjustability and most efficient head design have produced a longer, faster, more forgiving driver . . . a breakthrough in modern day driver performance.”

Breathtaking.

With the original I got down to and held a single-digit index for nearly a decade, albeit now a distant memory. Could Callaway do it again? Clearly, I was not alone in grasping at hope. Three days after the clubs were officially released on Aug. 28, the local Golf Mart sold out its allotment of GBB drivers.

From Harvey Penick to Hank Haney, instructors painstakingly explain that money is better spent on lessons than on promises made by new gear. The logical consensus is they are dead right. But golfers often are as illogical as Bizarro-Spock, easily separated from cash by shiny objects.

It’s also true that certain equipment can make a difference. A leather-covered feathery could never travel like a Pro V-1. Steel shafts proved far superior to hickories. And while the original Great Big Bertha is a technological relic by current measures, it was somewhat revolutionary, with a large Ruger Titanium head that induced a certain confidence on the tee, which then led to relaxed swings and consistent drives. It even sounded good, different from that click on the screws in a persimmon driver, but righteous.

I actually tried the original before it was even released, in a 1995 visit to Callaway’s spanking new headquarters and research center in Carlsbad, about 40 miles north San Diego. On assignment for Destination Discovery, a feature magazine then-published by The Discovery Channel, I was looking into whether “aerospace materials, designs and defense industry manufacturing techniques really make a difference in the Royal and Ancient game’s instruments of play?”

The research center did not disappoint. Stretched out was an eight-acre expanse of emerald fairways embedded with motion detectors, monitored by a trio of weather stations linked to banks of computers. The place swarmed with engineers and rocket scientists, some of whom actually did work on the sound of the ball leaving the clubface; one of my hosts was a post-graduate who had just earned a degree in applied physics.

The young physicist set me up in front of a system that measured club-head speed at impact, the ball’s launch velocity and rate of spin and its direction, an ancestor of the now-common Trackman. With a steel-shafted Big Bertha War Bird identical to the one I’d been using for several years, my swing speed averaged 88 miles per hour. He then handed me a Great Big Bertha, with a 265 cc head that was 25 percent larger than its predecessor, and a graphite shaft an inch longer than what was standard. With the same swing, the club came across the tee about 8 MPH faster, with a launch speed that would give me about 25 yards of additional distance. It also went dead straight.

Holy Ben Hogan.

Then came an additional bonus: “Mr. Callaway is in his office and said he’d love to have you come visit.” At the age of 76, Ely Callaway couldn’t force himself to retire. The former Burlington Industries executive and vineyard owner now ran a company whose drivers dominated the market. We chatted for at least an hour, although he didn’t want to talk much about the nifty new club, but instead about a book I’d recently co-authored on the business of the wine industry.

“We never claim that our drivers will make you a better player,” Callaway finally allowed. He then handed over sales figures and a survey that showed more than half of the pros on various tours were using Callaway drivers. “The clubs are demonstrably superior and pleasingly different.” Their popularity, he hinted with an arched eyebrow, is all one needs to know.

As I was leaving, he insisted I mail him an autographed copy of the wine book. Mr. Callaway, who died in 2001, never sent me a Great Big Bertha.

The GBB that was subsequently purchased served me well, and why I strayed into a fling with a Titleist is my shame. Oh, and then there was that Ping, picked up at a demo, which for awhile became a long, hot and straight companion until a Callaway Razr X came along and said “Hello sailor.” Last June the latter was stolen in Seattle and I wish its new owner nothing but hives.

There are many excellent drivers on the market, but I couldn’t seem to find one that suited me. Thus, the new Great Big Bertha came at an opportune time. During the launch, Callaway also introduced two versions of the Big Bertha Alpha, designed for better players. Although the company has had its ups and downs over the past two decades, the resurrection of iconic brand suggests that Callaway is rediscovering it place in golf under the direction of CEO Oliver “Chip” Brewer, who took over in 2012 after ten years leading Adams Golf.

“I think Chip took a hard look at the technology and clubs we’d been making, which were good, but thought we could do better if we put the best of what we had and more into the well-known brand names,” said long-time Callaway sales rep and club fitter Aaron Young, while setting me up with the GBB. “This one really does have more features than anything I’ve ever seen. And advance orders indicate it’s doing really well.”

The clubhead is a blend of aerodynamics and multi-material construction, and uses a system of internal ribs that run from the center of the interior sole to the clubface, which adds strength to the perimeter. The thickness of the face is variable and is thinner in strategic spots to expand the sweet spot. It features Callaway’s “Optifit Hosel,” with eight different ways to configure loft, lie and face angle. There is also a ten-gram sliding weight that moves on a track around the perimeter.

Over the past few years my drives have been fading, which was obvious to Young both in ball flight and on the Trackman. “You’re getting way too much side-spin and it’s really costing distance,” he explained. Young fine-tuned the lie angle and then slid the track over to the draw bias. Drives started and finished dead straight.

But range and the course are entirely different things. Over several rounds with the Great Big Bertha, I discovered that one could still dead pull a drive out of bounds. But on many holes with a relaxed swing, I was finding myself in places seldom visited, often 15 yards longer than average and on occasion nearly 30, where I could finally use an iron on a second shot.

Scores are three-to-five shots better than average, but it’s difficult to wholly link it only to straighter and longer drives. Pitch shots from 50 yards out have rolled up to kick-ins, and last week one dropped in for a birdie. Consistently getting out of bunkers has resulted in a few sandy pars, and putts that often just miss are falling.

So, perhaps confidence on the tee carries into other parts of the game. Or maybe Ely Callaway put in a word with the Golf Gods, asking them to cut me and my Great Big Bertha just a little bit of slack.